Few people with diabetes ever have diabetes alone. John Clements, assistant professor in MSU’s online Master of Public Health program, is turning to public health science to address diabetes outcome disparities for the elderly.

February 11, 2020

In 2012 in the State of Michigan, over 434,000 Medicare beneficiaries had a diagnosis of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. That’s a little over 30 percent of all Medicare beneficiaries over the age of 65 in the State of Michigan. Nationally, according to the American Diabetes Association, about 25 percent of seniors have diabetes. This is not a contest where we want to lead.

I’ve been working on an NIH grant-funded research project to learn more about disparities in diabetes outcomes based on race and ethnicity. In most cases, racial and ethnic minority groups tended to be worse off than whites, even when they had the same combination of chronic illness.

Few people with diabetes ever have diabetes alone, and we found that nearly 90 percent of our 434,000 beneficiaries with diabetes also had high cholesterol, high blood pressure, and were obese. So many people had these conditions that we didn’t even bother including them in our analyses.

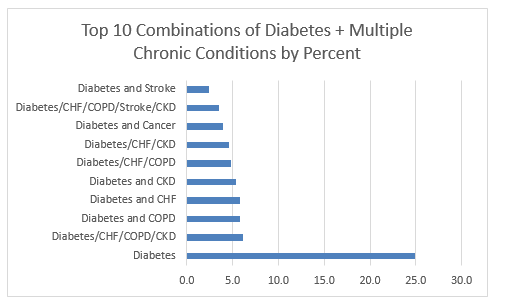

Instead, we focused on some leading chronic causes of death in the State of Michigan: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), congestive heart failure (CHF), chronic kidney disease (CKD), Alzheimer’s disease, Stroke, and Cancer. We found that about 130,000 or 25 percent of people with diabetes only had diabetes. The next highest percentage found 6.2 percent of people with diabetes also had COPD, CHF, and CKD…not one of these…all three of these.

People with diabetes are more likely to have a combination of these three chronic diseases than any other combination of illnesses.

- chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)

- congestive heart failure (CHF)

- chronic kidney disease (CKD)

Now here is the kicker, and unfortunately, it’s probably one that will not come as a surprise. In general, racial and ethnic minorities (except for Asian/Pacific Islanders) are at higher risk for having more chronic conditions, lower risk for accessing primary care prevention services, higher risk for using the emergency department, and incur higher costs for inpatient care. These patterns held when we accounted for combinations of chronic illness.

What this means is that when you compare a black man with diabetes and CHF, COPD, and CKD, who theoretically should be treated the same as a white person with diabetes, the black person still is worse off – they don’t access primary care, they don’t use prevention services, they incur higher costs – even when they have the same insurance.

Medicare is supposed to be the social safety net for seniors…an equalizer. It should provide the same access to care for everyone. I once was giving a presentation to a group of physicians about infant mortality in a community and was trying to make the point that black women start their lives with lower reproductive potential than white women and that their lives are filled with more risks from the time before they are born. An audience member made the argument that none of that matters because when they find a woman who is pregnant and uninsured, that they work to get them Medicaid so they can access care, and level the playing field.

The point I was trying to make is that a lifetime of risk for a pregnant woman can’t be adequately addressed if they get insurance and care for the first time in their lives when they are three months pregnant. I’ll make the same case here; seniors who otherwise don’t have insurance or who have inadequate insurance for their entire lives, can’t possibly make-up for a lifetime of not being able to access care just because they now have Medicare.

So the real question for me becomes, what do we do about it? In my mind, we have to start by addressing the social determinants of health and health literacy. Unfortunately, like most other institutions in the United States, it is difficult for racial and ethnic minorities to participate fully in the healthcare system.

There is a legacy of racism and unequal treatment in healthcare.

Until we address the issues that make groups of people in a society unable or unwilling to access care, we will never be able to address outcome disparities. I don’t know how we do that, but I do know it should begin long before the age of 65.

John Clements, PhD, Assistant Professor

Michigan State University Master of Public Health Program

College of Human Medicine